Further Thoughts On Martin Amis' Money

I finished Martin Amis' Money: A suicide note yesterday and I was impressed with the book.

However, I should say that if you want a happy book, then you should read something else. In an interview at the end of the audio version I heard, James Atlas call the book a chronicle of excess. I think that is accurate. And by excess, Amis refers not just to food, but also to sex. The concept of pornography, the idea and the reality of prostitution appear often. And the term "handjob" is a frequent one in the text.

Like Michel Houellebecq's The Elementary Particles or virtually anything by Dennis Cooper, Amis intends to provoke rather than uplift.

Let me say just a word or two about Dennis Cooper. His work is only for those who are truly brave . But let me go on for a moment about his work.

In 2015 Casey Michael Henry wrote an article in the New Yorker about Cooper's GIF project:

Cooper told me that he sees his GIF projects as continuous with his prose fiction, composed according to “the same principles and planning and structuring” as his work in print. Now sixty-two, he is best known for fiction that features clinical explorations of sex and violence. His Prix Sade-winning “The Sluts,” for example, details a fabricated murder scenario on a hustler message board. His most famous work may be a sequence of novels called the George Miles Cycle, published between 1989 and 2000, which follow damaged characters who seek the cipher-like figure of Miles, an actual person from Cooper’s life, who appears both as a character called “George Miles” and as a kind of abstraction—a symbol for the youthful purity that is inevitably ravaged by the needs of those who desire it.

To a younger group of writers who have come of age on the Internet, Cooper is known largely for his openness to contemporary novelty and an ethos of anything goes. A self-professed anarchist, he thinks of every writer as a “potential peer.” His blog, DC’s, is home to image-heavy posts on topics like esoteric spy technology and abandoned night clubs, and it provides an online meeting place for these young fans. It was here where I first “met” Dennis, as many do.

The blog also featured Cooper’s first “stacks,” or vertical columns, of GIFs, and early versions of chapters for his GIF “novel,” “Zac’s Haunted House.” The regulars at DC’s quickly took to the project, despite, or perhaps because of, its strangeness. Some critics have written appreciatively about it, too, though labelling the work has proven a challenge. In Bookforum, Paige K. Bradley wrote, “You could call Zac’s Haunted House many things: net art, a glorified Tumblr, a visual novel, a mood board, or a dark night of the Internet’s soul.”

In 2015 Cooper's blog that he hosted on google was deleted by google. This move generated a lot of interest in some segments of the literary community. See for example this article in the New Yorker and this article in the New York Times.

OK. That was Dennis Cooper. Let me move back to Martin Amis and his novel.

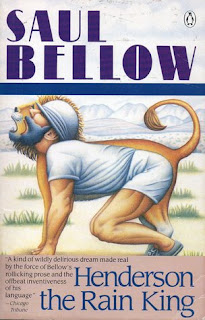

Like many contemporary novelists, Martin Amis's writing owes a debt to his literary heroes. Saul Bellow is one of Amis's favorites. Money reminds me of the start of Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King. It is important to bear in mind that Amis was friends with Bellow. The beginning of Henderson, with all of the narrator's complaints about his life, certainly seems to me to be similar to Money.

What made me take this trip to Africa? There is no quick explanation. Things got worse and worse and worse and pretty soon they were too complicated.

When I think of my condition at the age of fifty-five, when I bought the ticket, all is grief. The facts begin to crowd me and soon I get a pressure in my chest. A disorderly rush begins -- my parents, my wives, my girls, my children, my farm, my animals, my habits, my money, my music lessons, my drunkenness, my prejudices, my brutality, my teeth, my face, my soul! I have to cry, "No, no, get back, curse you, let me alone!" But how can they let me alone? They belong to me. They are mine. And they pile into me from all sides. It turns into chaos.

Let me say that the complaining about teeth must have been personal for Amis. In his memoir Experience, he goes into detail about his dental problems. They were serious. Enough said.

On to a few thoughts about the novel Money. Here is what the narrator says about the process of being robbed:

Jesus, I thought, it's guilt welfare. People get on just fine with their money, but when someone genuinely needy shows up, with a big knife, they get all these new ideas about the distribution of wealth (p. 282).

Or consider what the narrator has to say when he is about to board a plane:

Manhattan, JFK, you know these are suddenly different places when you have no money. You change, but they change too. Even the air changes. I felt it the instant I stepped out of the Carraway. With money, double-dazzle New York is a crystal conservatory. Take money away, and you're naked and shielding your Johnson in a cataract of breaking glass. Each sound and smell and stare is that much harder to hold. It's a tough town. I see that's all true now. Tough? It's a fucking shitstorm! Near the knuckle is the only place where things really happen. It is a lot more vivid, a lot more realistic down here. And you need to deal with new kinds of moneymen, talented milers in sensible suits, who jink with change and moneykeys as they run grunting in your wake (p. 326).

Ok, that is the concept of money. Let me say a word or two about the character and character names. In the interview I mentioned earlier, James Atlas interviews the late Christopher Hitchens about the book. Hitchens was a friend of Amis and was very familiar with his work, but an interview with Amis would have been expected. Anyway.

The main character and narrator of the novel is John Self. And Martin Amis makes an appearance a few times. In fact, Self hires Amis to ghost write the screenplay that he (Self) was supposed to write. Perhaps you have read Philip Roth's Operation Shylock in which Philip Roth realizes that there is another man using the name Philip Roth in an attempt to lead the Jews out of Israel and back to Europe.

As far as the name John Self, Hitchens had two thoughts:

- Amis spent a lot of time coming up with names for characters.The name always tells you something important.

- The fact that the character is named Self is a clue as to the fact that this may well be an unreliable narrator.

The idea of unreliable narrator was a very important idea for Vladimir Nabokov, a friend and large influence on Amis. Nabokov explored this idea in many of his books, but, at least for me, the idea reached its zenith in Pale Fire.

Just describing the book gives you a clue as to how unusual the book is. The book claims to have two writers: John Shade and Charles Kinbote. The book has four sections: an introduction (written by Kinbote), a 999 line poem (written by Shade), endnotes commenting on the poem, and an index (both writen by Kinbote). Scholars divide into Kinbotteans, and Shadeans depending on who they believe is the author of the text. And, if that is not complex enough, Brian Boyd in his book on Pale Fire claims that the narrator may well be Hazel Shade, the deceased subject of the poem and daughter of John Shade. Decide for yourself.

Saul Bellow and Vladimir were literary giants. I would argue that Martin Amis's Money is just as worthy of reading as their books are.

Comments

Post a Comment