Ten Favorite Books from the First Part of 2022

The late Roger Ebert -- a hero of mine -- once wrote that ever since Moses came down from the mountain with the ten commandments that critics were required to compose a list of the ten best movies of the year. Clearly, Ebert was not a fan of the idea; nevertheless, he composed such a list each year, even if he often listen many more than ten pictures.

In this post I thought I would share a list of ten books I have read so far this year that I particularly enjoyed. Since ten is never enough in a list or listicle, I also included five more books that I thought were also good. The list is in order of when I read the books; I take no position on how the books might be ranked.

Hell of a Book by Jason Mott

Mott's book is an experimental book about a man on a book tour promoting his book, Hell of a Book, and a story of an African-American boy named Soot who is being bullied on the school bus. Mott's book reminds me of another great book, Paul Beatty's The Sellout. Beatty's book is also an experimental novel written by an African-American man which foregrounds the Black experience, in Beatty's case the issue is slavery, in Mott's case, the issue is Black Lives Matter

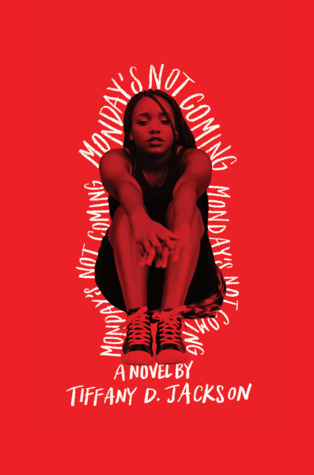

Monday's Not Coming by Tiffany D. Jackson

Jaskson's novel is a young adult novel about trauma and teen mental health in a Black neighborhood in Washington D. C.. The novel also features an unreliable narrator, an underused technique.

Unbeatable Squirrel Girl: Big squirrels don't cry by Ryan North

The only comic book on my list. I have a pile of them on my iPad; I do need to read more comic books. For me, at least, this book is laugh out loud.

Mercy Street by Jennifer Haigh

A novel about a woman who works in a clinic in Massachusetts that provides abortions and her quest to find meaning even if that meaning does not seem to come. I think Haigh's book has new significance since the Dobbs decision changed the nature or women's health care in this country. For a book that foregrounds abortion and the politics around it, the story is a surprisingly quiet one.

The Unwomanly Face of War: An oral history of women in World War II by Svetlana Alexievich

It is hard to overstate just how important the World War II or, as it is called in Russia, the Great Patriotic War affected life there. Compelling

Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the siege of Leningrad by M. T. Anderson

Anderson's book, written for young adults, provides a completely different perspective on the war from the one Alexievich gives. Shostakovich was, arguably, the most important composer in Soviet history, even if he had a very complicated relationship with the Soviet state. The book gives a lot of background about arts in the early Soviet Union including people like the poet Anna Akhmatova.

Disorientation by Elaine Hsieh Chou

First, it is worth taking a moment to admire the book cover. Do take a close look. And do take a minute to think about what this image might mean.

Second, Chou's book is a book about graduate school and the nature of culture, language, and identity. These are concepts I, personally, have spent decades thinking about, and I think Chou had important things to say about what it means to be an American writer from Taiwan.

Aviva vs. the Dybbuk by Mari Lowe

Lowe's book is written for children; it is a book about trauma within a small Jewish community. Aviva vs. the Dybbuk also features and unreliable narrator.

The Age of Phillis by Honoree Fanonne Jeffers

The only poetry book on my list. Jeffers' book dives deep into the life and work of Phillis Wheatley. Wheatley was born in Africa, captured and made a slave around the age of eight. She also was the first known African-American to have published a book of poetry. And she died in obscurity around the age of 31. Jeffers does several things in this book: she argues for a richer and more complicated biography of Wheatley than others have provided, she imagines a range of poetry Wheatley might have written, and she also creates some very good poetry in a variety of different forms and genres.

Borgel by Daniel Pinkwater

Daniel Pinkwater remains a national treasure of children's literature. Borgel is, I suppose, a book for young adults about a road trip with a twelve year old boy and his, um, unusual, 111 year old uncle. Here's an earlier post I wrote about this book.

The runner ups.

Like Ebert, I find 10 to be a more or less random number. Here are five more books I enjoyed almost as much this year so far.

Razorblade Tears by S. A. Cosby

A great crime thriller. Roxanne Gay offered the following quick review:

Stayed up all night because I couldn’t put this book down. Action packed, a fine hard edge of a story about two very flawed fathers seeking justice for their murdered sons. Really well written and absorbing. I would have liked to see more attention paid to the women characters who were not well fleshed out. And there were parts that were overly didactic about accepting (or not) LGBTQIA people. But this is an explosive thrill ride. You will love this novel.

Chester B. Himes: A biography by Lawrence P. Jackson

An in-depth biography of a writer who lived and wrote about prison, sexuality, the African-American experience and other things. Himes is perhaps best remembered for Cotton Comes to Harlem. He should be enshrined in the cannon.

New from Here by Kelly Yang

A pandemic novel for children. Yang's earlier novel Front Desk was also great.

Thank-you Mr. Nixon: Stories by Gish Jen

A collection of stories about how China has changed since first opening up to America and the so-called Western world since the Nixon administration.

The North Water by Ian McGuire

A real crime adventure story that has elements of Jack London and Herman Melville. Here's an earlier post about the book.

Comments

Post a Comment